2 Years, 2 Weeks, 2 Hours

- Tracy Dong

- Jul 10, 2023

- 9 min read

“We forget about the past and just keep moving on” my father would tell me when I was a little girl. A voice and mantra that revisits my consciousness as I grow older. Difficult relationship? Friendship falling out? “Just forget about it, work harder and move on”.

My parents spent most of their adulthood escaping terror, living under governmental oppression, and hanging on to their lives. There was no time or space to think about anything else but to survive and make a living. I was not brought up to deal with emotions, but to deny, suppress, and abide by filial piety. I listened to this voice perhaps more faithfully than I had hoped, as I reached adulthood with knowledge of my own family history forgotten or not even known.

Reaching my late-twenties, and two years into a pandemic isolated with my own thoughts, existential inquiry turned into a daily rumination. Whiplashed into an undertow of self-examination and excruciating clarity, fueled by the recent rise of anti-Asian hate crimes. Twenty-something years of keeping my head down, working myself into exhaustion to scrub off the label of “not belonging”, overcompensating in every aspect to “fit in”. How could it be that when I finally look up, with two degrees, a job at one of the most valuable companies of our time, and above-average financial freedom for my age, that I feel emptier than ever? I had been searching for the substance of life’s meaning to fill the gaping void in me, further away from home in the crevices of the world.

My father ran away from the Vietnamese Communist government, away from the horrors of warfare so that me and my sister could lead better lives. So, I ran with him, but I kept running. Away from him, my home, and now seemingly from myself. I’ve skimmed through every region of the US in temporary living situations never lasting more than two years. I have a mysterious urge to traverse the world on my own, taking myself to dangerous situations in Africa, the Middle East, and South America to find something. That something always seems to be missing. I find myself now in New York City, a city that is finally big enough for me to keep running. Running to find something to heal my inability to connect, lost somewhere at sea among the boats that carried my family to escape. This run-down desolate heart lacking rootedness, subconsciously escaping from itself, searching for meaning further and further away, realizes it must return to where the start of healing conspicuously is – home. So, as the COVID travel restrictions relax, and the international borders open again, I book the trip to return home to Vancouver.

Having a war veteran as a father, our relationship has always been estranged. His remnants of emotional PTSD un-shackled with frightening temper, and extreme paranoia had left an enduring mark on my perception of love and sense of self. After two years apart from the pandemic, it seems to be the absence of empathy that had been gating my ability to fully embrace compassion, forgiveness, and reconciliation. I had to learn my family history in order to understand myself. I needed to hear his story. We finish our bowl of phở, pour some tea, and engage in what comes out to be a two-hour conversation about his past and time in the war. At 26 years of my life, this is the first time I have ever heard this story in its entirety.

My father fought for South Vietnam for about five years: 18 months in the military academy and three years as a second lieutenant for the platoon of Quảng Nam province in Central Vietnam. After South Vietnam fell to the Communist North in 1975, he became one of the 2.5 million South Vietnamese soldiers captured as a prisoner and held in “Trại học tập cải tạo”, detention camps run by the North Vietnamese in the jungles of Central Vietnam. He was sentenced to 3 years, subject to back-breaking labor, little food, and violent treatment as a means of revenge and indoctrination of new government principles.

After his release in 1978, he could finally come home to what is now called Ho Chi Minh City, however life was not the same. Any former South Vietnamese officer, referred to in Vietnam as the “American ally”, and their family members of the “enemy” would face potentially a lifetime of discrimination. We would be denied access to employment, education, health care, and any other government-backed benefits. He spends another decade working under a different name, saving up every penny, and attempting multiple escapes. By 1989, my mother, father, and sister finally left the grips of their war-torn home and escaped on an over-crowded 15-meter-long, 4-meter-wide boat with 135 other people, to seek life in a new land. Trepidation and proximity to death did not end there, as my family had to endure life at sea with broken engines, rising water, a raid by Thai pirates, and three years in refugee camps in Malaysia and Indonesia. They finally arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1993, and I was born in 1995.

Who were you before the war?

“I lived in Saigon with my parents and 10 siblings. I practiced martial arts, and just focused on studying. I wanted to become a lawyer. It was 1972 when the North Vietnamese crossed the 17th parallel into South Vietnam, and the War had become more serious. I was in my second year of law school when I was drafted into the War.”

What happened after you were enlisted?

“After three years in the academy, I was promoted to second lieutenant for the 14th Battalion in the Quang Nam province. I was the leader of the platoon with 36 soldiers under my direction. I led the soldiers into combat, gave orders, but most importantly, I made sure each one of them were trained to a high state of combat readiness. For three years during battle, we never slept in beds. We had to sleep in holes we dug into the ground. We were constantly on the move, and on the lookout for Viet Cong guerrilla forces. They would hide in the jungle and set up traps (sharply pointed bamboo that could pierce through the thickest of soles, nooses hidden under foliage that can hoist victims 30 feet in the air). I had to be on high alert all the time.”

What happened to you after the war ended?

“After April 30, 1975, the North took over South Vietnam. I was forced into a detention camp for three years. I was given only one suit of clothes for my whole time there, a brown and white striped prisoner uniform. Most of my work was to cut down trees and transport lumber. At times we’d have to cross rivers where the water would reach my chest. I’d dry my only set of clothes in my tent. We were treated worse than prisoners. When I was released in 1978, my life did not return to normal, as the new government treated me differently because of my history as an officer. I had to report to the government day and night about my daily activities. I had my valuables confiscated. I could not find work, I had to use my mother’s last name to work secretly at a soap factory. I had to burn the photos and any record of myself of who I was in the war. I saved up gold that I earned at the factory to use as a bribe to escape the country by boat. Finally, in 1989, after five attempts, me, your mother and sister escaped on a boat with 135 other people.”

What happened at sea?

“Once we crossed into international waters towards Malaysia, the engine died, and water came pouring into the boat. Immediately I thought we were going to die. I remember crying and praying out at sea. In these moments, I felt regret for bringing your mom and sister with me, risking their lives. I could’ve gone by myself and came back for them. While the engine was out, it felt like we were waiting for our death. Then we saw a boat approach us, it had a Thai flag. They told us they would rescue us and bring us food and water. Once they were on our boat, they took out their guns and that is when I realized they were pirates.”

I could sense that I was spared the details of what came to be of this horrific scene. I am flooded with anger, agony, and sympathy for what my family had to endure. I want to cry into my dad’s arms and tell him I’m sorry, but I don’t, because that is not how our relationship is.

“The mechanic of the boat told your mother and sister to hide under a large oil tank, so they did, and they were spared. I remember at this moment, I prayed three times ‘Nam Mô Quán Thế Âm Bồ Tát’, (in Vietnamese Buddhism, this is the prayer to the Bodhisattva of Compassion). These are the same words that saved me from dying at battle. Suddenly, one of the girls from our boat spoke up. She could speak Thai. After she spoke to their captain, we were let go. It was truly a miracle. Sometimes I think that she was a reincarnation of Quán Thế Âm Bồ Tát’ to save our lives.”

“After one more broken engine, a brief stay in Malaysia, we set sail again and ended up in Indonesia. We had one more scare, as of August 12, 1989 all refugee camps closed in Southeast Asia. However, since I have a history of political discrimination, we were able to enter as asylum seekers who were forcibly displaced. I was interviewed by the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) to screen for political refugee status. We became part of just the 20% of the 135 people onboard to make it into the camp. It is at the GaLang Refugee Camp where we spentd 3 ½ years. At this point, we were severely malnourished. Each family was given just one cup of tea, and one bowl of rice with fish, per day.

What are some of your most profound memories from the war?

“I will never forget the day we finally arrived in Canada, June 30th 1993. A Vietnamese-Christian church offered to sponsor us, and we arrived by plane. I will also never forget one day as platoon leader, in the battle of Dai Lộc in Central Vietnam. One night, as I was leading 20 soldiers into settlement, we got ambushed. We immediately lost 6 guys. All through the night, we had to stay awake and alert. The only way to find a way out was to charge straight towards the enemy. 12 of us survived.”

When I asked what advice he would give to his younger self, the words “fight”, “work hard” and “never give up” came up repeatedly that I almost didn’t hear anything else. The words that carried my dad through to survival at war and at sea. The words that pushed me to independence and making a living for myself. Words embedded into my subconscious that I feel gratitude and anguish with.

Do you feel like a different person now compared to who you were before the war?

“For the most part, no. Most of my friends were either amputated or had died. So, I feel extremely lucky. For the ones who are still alive, I want to come back and help them financially. There is still some anti-South Vietnamese sentiment back home, and I still have nightmares. I always try to forget about the past, and only look to the future. If you keep thinking about the past, you will never succeed.”

My father continues into a tirade about how beneficial forgetting the past is. I’ve heard this before. I am confused and slightly frustrated with his answer. Does the trauma resurface after denying it for so long? Are you at peace? I didn’t know a lot about his story until now. I don’t ask these questions out loud, as I know he will misunderstand where I am coming from, but I understand him a little more. Perhaps he had been trying to protect me. Perhaps that was his way to show love.

That was two hours.

The longest conversation we’ve ever had. We don’t talk much in our relationship, but after we wrapped up our meal and tea, I could sense there was something in the way we cleaned our dishes together that we were a step closer to reconciliation.

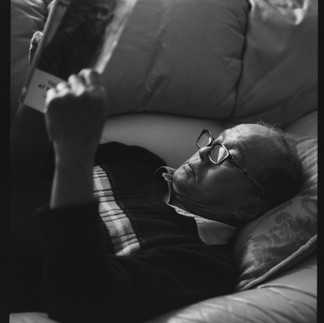

Dad walks over to his piano and starts playing. Music was always his way to enter his own world and heal from his past.

If it were possible to extract the fundamental realization that has come out of my time here in brief - it could be this. To come from a country whose history is war, 1000 years under the Chinese, 80 years under the French, decades under the Americans by the Vietnam War. It is not of my life to carry on a personification of a long and tragic history of struggle, but one a nation’s proof of resilience. The inception of that thought signaled to me that I was no longer ashamed of where I came from.

I hang on to the words of beloved Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, “the ocean of suffering is immense, but if you turn around, you can see the land.” I guess it was never too late to turn around.

Tracy Dong is a Vietnamese Canadian portrait and documentary photographer and visual artist, currently based in Brooklyn, NY.

Tracy’s work focuses on evaluating the vulnerabilities, complexities, melody, and motion of the human condition, with an emphasis on representing the Asian diaspora experience and LGBTQIA+ communities. Connect with Tracy on Instagram or visit www.tracytdong.com.

.png)

Comments